The End of History?(?)

In the summer of 1989 Francis Fukuyama published an influential article called “The End of History?” He argued that, from the perspective of political philosophy, the growing rejection of communism in Eastern Europe potentially represented “the end of history.” At first blush, it seemed like so much bombastic Cold War propaganda. But he was building on an “end of history” claim Hegel had made two centuries earlier.

By the fall of that year, the Iron Curtain was collapsing. Fukuyama’s article became synonymous with the conviction that democracy and capitalism had finally and definitively defeated other ideologies. His argument was more nuanced than that, but he did initially buy into the notion that political liberalism follows economic liberalism. And he saw consumerism as a driver of economic liberalism. In that sense, his views were the natural outgrowth of the Chicago School thinking of the era, where the human being in the economy is little more than a consumer.

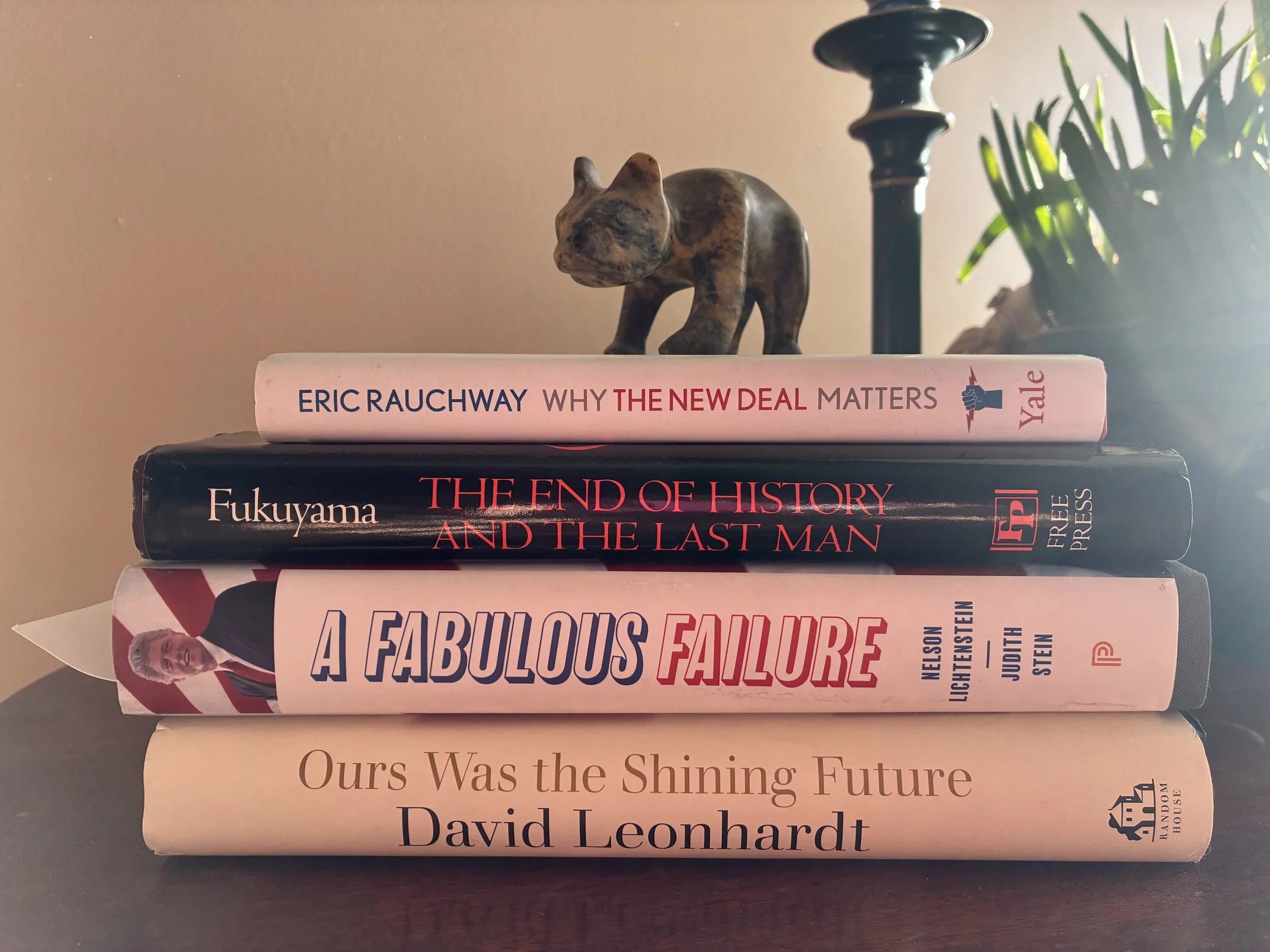

Fukuyama followed up in 1992 with a book, The End of History and the Last Man. The book is different in important ways from the article, and it gives us insight into how we went wrong — and why so many of today’s leaders, whether in politics, journalism, or academic institutions, struggle to meet the moment.

Liberal Democracy and Capitalism Are Not the Same Thing

In “End of History?” Fukuyama accepted the proposition that political liberalism follows economic liberalism. In the book, he recognizes that it is indeed possible to have economic liberalism — and prosperity — without freedom. Critics (and supporters) of Milton Friedman may immediately think of Pinochet’s Chile and “the Chicago Boys.”

Fukuyama’s change in thinking is significant because the view that one led to the other was cover for the advancement of Washington Consensus policies, like the WTO and the PRC’s subsequent accession. That was not Fukuyama’s fault, though he is often saddled with the blame: he had already corrected the record. But trade policy by meme, a favorite of the econ/foreign policy blob, had overtaken the discourse.

Had we not been so smitten with a false premise (that, by the way, neatly served the interests of multinational corporations), we might have taken a look at the last time the United States thought deeply about trade and democracy. But we didn’t. Instead, we invoked the rhetoric of FDR, without the substance — and pushed out trickle-down economics at scale.

Man is Motivated by Economic Well-Being and Dignity

Having recognized that capitalism does not necessarily lead to political liberalism, Fukuyama then spends time revisiting the question of whether man is motivated solely by material welfare. Here, he goes back to Hegel and notes that while man is indeed motivated by his economic condition, he is also motivated by what Hegel called the struggle for recognition, what Fukuyama describes as dignity, and what we might today call feeling seen. This side of man, not the economic side, is, according to Fukuyama, the political side.

Part of his project in writing the book was to recover “the whole of man, not just his economic side.” He shows the limits of seeing the human being only as an economic actor — only as a consumer. His former neoconservative self even refers to the “dignity of the worker”! He notes that Martin Luther King Jr., spoke of dignity in parallel with economic well-being. The civil rights movement was not only a civil rights movement. It was an economic movement, too. Because King saw the whole of man.

The End of History is Stultifying

Even with its limited but mistaken triumphalism, “End of History?” recognized that the end of history is not nirvana. Once the struggle of ideology is over, and material wealth is achieved, a sort of banal complacency sets in — comfortable, but boring.

Drawing on Nietzche’s concept of the Last Man, End of History predicts that “We risk becoming secure and self-absorbed last men, devoid of . . . striving for higher goals in our pursuit of private comforts.”

What Does this Mean for Us Today?

Fukuyama’s own evolution is instructive. A neocon at the time he wrote the article and the book, he came to reject that world view, railed against Reaganism and Thatcherism, and warned that Chinese state capitalism could represent precisely the kind of ideology that might challenge his End of History thesis.

“We risk becoming secure and self-absorbed last men, devoid of . . . striving for higher goals in our pursuit of private comforts.”

Not long after he spoke those words, the pandemic proved a test case. The PRC mishandled it and had persistent lockdowns. The United States — having moved away from neoliberalism and re-embraced Keynes and FDR — outperformed the PRC.

Now comes 2025, where the United States is embarking on a course of unprecedented self-harm, while also inflicting harm on others. Yet leaders in many corners of the world, including at home, seem fundamentally ill-equipped to meet the moment.

Here is where End of History may have the keenest insight. For three decades, there has been no serious ideological struggle in the West. Many of our leaders have no idea what ideological struggle looks like, let alone any sense of how to fight in one. The End of History seems to have bred precisely the complacency and self-absorption that Fukuyama warned about.

“Yet the instinct of the last-mannish political consultant class is to lable these affronts to dignity ‘distractions.’”

The conviction in some quarters is that politicians should just sit on the sidelines and wait for the the economy to implode. That approach validates the concern that motivated Fukuyama to write the book; a “lay low” political strategy, if it can be called a strategy, focuses on economic man to the exclusion of his political side. It is true that cost of living is a core issue that has to be addressed: Zohran Mamdani has focused on it in the high-profile New York mayoral race. But we need not do it to the exclusion of the other things people care about. They’re howling about concentration camps, cruel deportations, abductions, militarization of cities, and leniency for child sex-traffickers. They are outraged about things that have nothing to do with the price of eggs -- yet the instinct of the last-mannish political consultant class is to label these affronts to dignity “distractions.”

Reading End of History in 2025, you can’t help but see our predicament through the book’s lens: material well-being has made a lot of leaders soft.

New Deal Capitalism

In the book, Fukuyama takes for granted that New Deal capitalism was the capitalism of liberal democracy. He felt, as many of us did, that it was “largely invulnerable to rollback.” But even Democrats found it fashionable to dunk on the New Deal: in discussing the economy, one 2020 Democratic Presidential candidate referred to “some of the excesses of FDR’s era.” Which ones might those be? Labor laws? Social security? Unemployment benefits? Bank regulation? Antimonopoly policy?

And this is where many Democrats have drifted: away from the policies of the era that incubated the Golden Age of Capitalism, the burgeoning of the middle class, and the American Century — all the things that allowed us take our democracy for granted — toward the Darwinian capitalism of Milton Friedman. As we think about the relationship between capitalism and democracy, let’s not forget that Friedman criticized one-person one-vote when he was in apartheid South Africa in 1976.

Fukuyama is no longer a neocon and now calls himself a social democrat — another way of describing a New Deal capitalist. Democrats who consider themselves left of center but are right of Eisenhower are having a meltdown over Mamdani, but even Bill Kristol — whose father published Fukuyama’s article — says he prefers social democracy to corporate authoritarianism. He said it after Davos!

If, as we approach our 250th birthday, we want the American experiment to succeed, then we should commit ourselves to giving liberal democracy a fighting chance to be the End of History. That means doing the hard work of perfecting our union, of addressing the inequality aggravated by decades of bipartisan adherence to Reaganomics, and of remembering that while pocketbook issues matter, so does dignity. Our job is to appeal to the whole of man.

That means throwing off the mantle of the Last Man, believing in something, and fighting for it.