On Elitism

In July, Dave Dayen, Executive Editor of the American Prospect, warned that the Epstein scandal wasn’t going away because it is about more than the trafficking of girls – it is about elite impunity. He was right. It sheds light on our current political challenges, so much of which are about elite dominance.

Even as this scandal continues to roil, Democrats are fighting about whether the party should shift to the center or to the left. One 2020 Democratic candidate who argued that we needed to move away from the “excesses” of the New Deal also contends that we spend too much time on “identity” politics. It’s elitist, and it’s exactly why Democrats struggle to form the kind of lasting support that can survive any given election cycle.

We don’t have to look back too far to see what a winning formula looks like. The New Deal is exactly how Franklin Roosevelt began to develop a multiracial base that sustained Democrats for half a century, until the beautiful people who thought the New Deal was “excessive” got hold of the Presidency and promptly lost the House for the first time since the Truman Administration. That loss opened the door to the Contract with America, which, today, looks more like a contract on America.

FDR’s Base

On the heels of the 1929 crash and the ensuing Depression, Roosevelt, himself a product of elitism, was a class traitor and directed his pitch to working people. It is because his pitch was aimed at working people that he started to attract support from the Black community.

“That, too is a lesson: whatever your base, don’t take their support for granted. ”

Until 1932, Black voters tended to support Republicans as the party of Lincoln and of emancipation. Backing Roosevelt during the 1932 election, prominent Black lawyer and Philadelphia Courier editor Robert Vann, himself a former Republican, reflected that Black people “know the difference between blind partisanship and patriotism.” Despite the racist construct of the New Deal, the overall economic agenda was beneficial to Black families, and Eleanor Roosevelt used her perch at the White House to advocate for civil rights. By 1936, FDR was able to begin to consolidate support in the Black community.

Nevertheless, Vann became disillusioned and in the 1940 election threw his support to Republican challenger Wendell Willkie. That, too is a lesson: whatever your base, don’t take their support for granted.

True consolidation of Black support within the Democratic Party did not occur until the 1960s, however. A month before the 1960 Presidential election, when Martin Luther King, Jr. was jailed in Georgia for defying Jim Crow, John F. Kennedy reached out to a pregnant, anxious Coretta Scott King. That show of support resonated, and Kennedy won the election -- securing a significant number of Black votes.

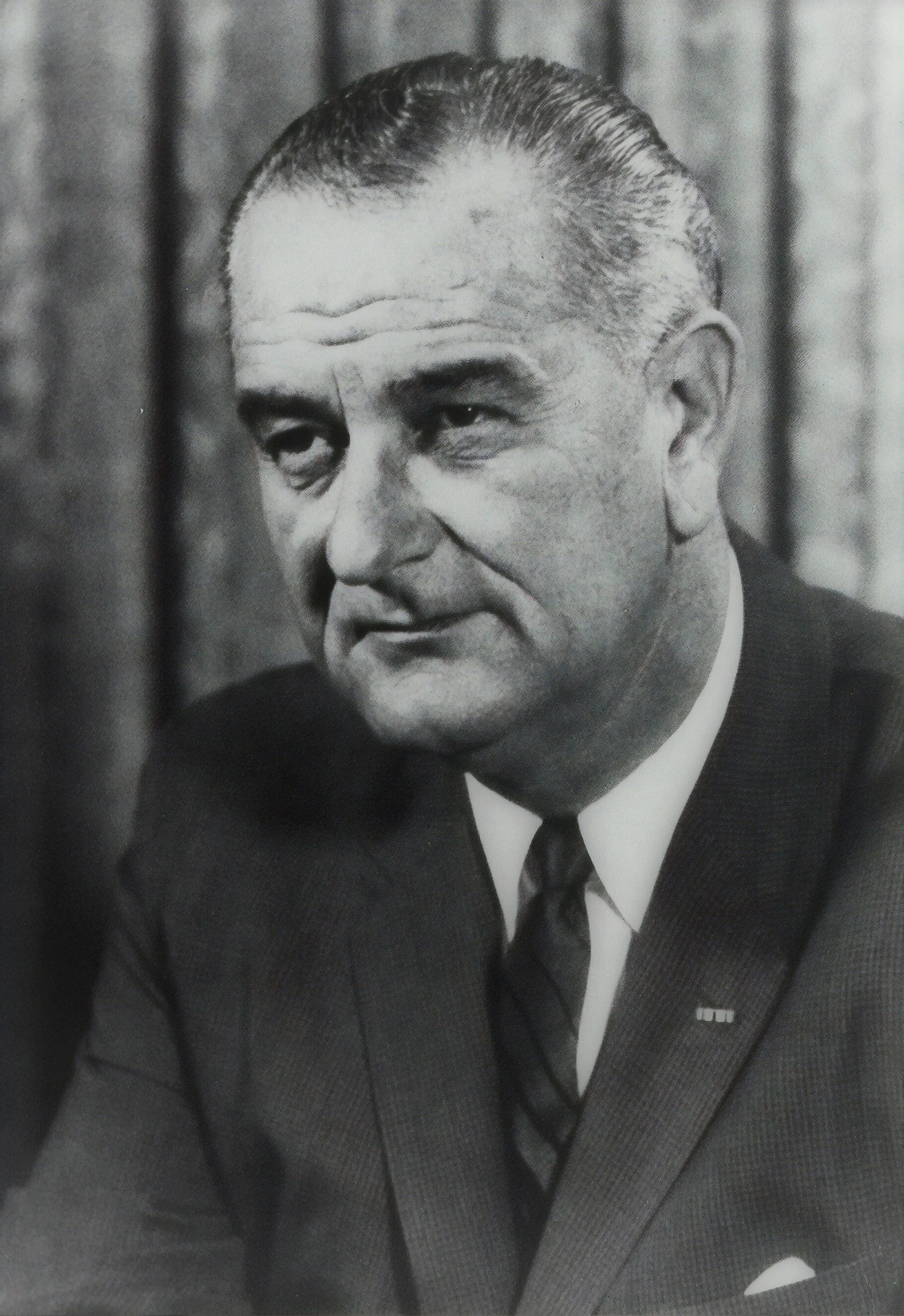

In 1963, Lyndon Johnson took office after Kennedy’s assassination. LBJ’s early exposure to rural life and poverty in Texas influenced his views of governance. He pursued a program of civil and economic rights even as Barry Goldwater pursued one that, in the words of MLK, “articulates a philosophy which gives aid and comfort to the racists.” In the wake of Selma, LBJ immediately pressed for what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1965. He contended that:

This great, rich, restless country can offer opportunity and education and hope to all – black and white, North and South, sharecropper and city dweller. These are the enemies: poverty, ignorance, disease. They are the enemies and not our fellow man, not our neighbor. And these enemies too – poverty, disease and ignorance –we shall overcome…. There is really no part of America where the promise of equality has been fully kept. In Buffalo as well as in Birmingham, in Philadelphia as well as Selma, Americans are struggling for the fruits of freedom.

This is one nation. What happens in Selma or Cincinnati is a matter of legitimate concern to every American…. [L]et each of us put our shoulder to the wheel to root out injustice wherever it exists.

The Centrist Proposition

In light of that history, it is baffling that some Democrats are arguing that the solution is to jettison both the working class and to stop recognizing racism (and sexism and xenophobia) as problems in our society.

Who, then, is the base of the party going to be? Republicans?

Let’s examine how the Democratic shift to Reaganomics in the 1990s has worked out for us 30 years later:

Dismantling constraints on media ownership means we have alarming concentration across different platforms that threatens our very democracy;

Dismantling constraints on capital means we blew up the global economy in 2008 and returned to the boom/bust cycle of capitalism that led to the New Deal in the first place;

Bailing out bankers after the 2008 crisis while indulging austerity whisperers means we stoked working class rage, which in turn fed the Tea Party movement (since captured by monied interests);

Concluding trade agreements that used New Deal messaging while ignoring New Deal policies means the party’s working class base continues to feel betrayed by the party that was supposed to be on their side.

This is elitist policy at its finest. If you look at the Epstein files, you won’t have to work hard to find some of the architects of that policy.

Democrats used to know that unfettered capitalism sows the seeds of its own demise. It tends toward excess, taking advantage of the opportunity to exploit for profit. Race-based chattel slavery, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the gold standard, the model of trade agreement generated by Reagan and embraced by Clinton – all of these policies privilege capital at the expense of labor. End-of-History author Francis Fukuyama thought we’d mapped out a form of liberal democracy that couldn’t be improved upon. He later realized that, for that theory to hold, liberal democracy must rest on the types of policies FDR put in place to prevent capitalism from consuming itself.

It’s Class and Race

The New Deal was a template for a set of economic policies that would shrink the widening inequality gap. Labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph understood that the civil rights movement and the labor movement were a symbiotic effort. He built on his successes with the FDR and Truman Administrations and in 1963 realized his two-decade-long goal of having a March on Washington. It was, in fact, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Jobs and freedom — yet the “jobs” part of that historic day has dropped out of the mainstream discourse. Too many of us think it was only about civil rights, and too few of us know that Martin Luther King, Jr. was only in Memphis that fateful day because he was supporting striking sanitation workers.

“The severance of economic and civil rights is a convenient cleft for elite Democrats who want to reap the economic benefits of Republican policies but don’t see themselves – or don’t want others to see them — as Republicans. ”

The severance of economic and civil rights is a convenient cleft for elite Democrats who want to reap the economic benefits of Republican policies but don’t see themselves – or don’t want others to see them – as Republicans. They distinguish themselves by supporting racial and other forms of equity, when convenient, while benefiting from an economic structure that exacerbates class and racial tensions.

Now, though, it seems they’re prepared to skip the equity part, too. It’s what happens when you don’t believe in anything other than your own status. Elitism strikes again.

Distributional Effects of Elitist Trade Policy

It’s commonplace to think that FDR was a free trader and that the progressive thing, therefore, is to also be a free trader. FDR wasn’t a free trader in the way we talk about it today, but more importantly, the “free trade” agreements of the neoliberal era are profoundly elitist.

The results prove it. When we were in office, one of the first things Ambassador Tai did was to ask an independent agency to study the distributional effects of U.S. trade and trade policy on U.S. workers. As it turns out, that policy was bad for both communities of color and non-college educated white men. This is a class and race problem, not a class or race problem.

The current folks put an end to the study, which was supposed to be repeated every few years.

Why?

The Class/Race Wedge

Not for the first time in history, elites realize that they can divide and conquer along class lines – by deploying race as a wedge. That’s what the “culture wars” are. It’s what felled the progressive movement at the end of the 19th century.

The divide-and-conquer strategy is working again, though, thanks to the Democratic merger with Republican policies that left working people behind. Those policies provided fertile ground for angry working class voters to direct their rage at people of color and immigrants. That austerity-to-racial-hostility pipeline is a familiar one: see Germany in the 1930s. And Germany today, after the puzzling repeat of history in response to the sovereign debt crisis of the 2010s.

Solidarity as the Way Forward

“The fundamental mistake we made during the neoliberal era wasn’t spending too much time talking about “identity;” it’s that we thought we could have a New Deal coalition based on Reaganomics. ”

The fundamental mistake we made during the neoliberal era wasn’t spending too much time talking about “identity;” it’s that we thought we could have a New Deal coalition based on Reaganomics. Now that race has once again been weaponized to divide the working class, the answer from Democratic centrists is to stick with Reaganomics and quit talking about identity. Ok, but that makes you a Reagan Republican. Not even an Eisenhower Republican! He was too far to the left for today’s centrists!

History tells us that the answer for the Democratic Party is just the opposite of giving Ronnie a big hug: reject trickle-down economics and embrace a coalition of the people who’ve been left behind. Rebuild solidarity across the working class. That means also owning that some of those who have been left behind were left behind because the economy was structured to leave them behind.

If you want to advocate what passes for “centrist” economic policies, and you don’t want to talk about race, then instead of dragging the Democratic Party further to the right, why not direct your efforts toward rebuilding the old Republican center? They could use the help.